What are Pass-Through Certificates (PTCs)?

Introduction

Financial engineering has become a powerful mechanism in structured finance, to bridge liquidity gaps, restructure risk, and create marketable securities from previously illiquid assets. While the intent behind financial innovations was to create value, they’ve also been at the center of significant misuse, particularly during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. The global financial system was shaken by the collapse of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). That event raised questions about the true safety of these financial instruments and the inherent risks of securitization. Looking back, the lesson was clear: innovation in finance is a double-edged sword. If wielded with care, it can provide substantial benefits. However, when driven by greed or carelessness, it can bring about financial catastrophe.

Pass-Through Certificates (PTCs) have emerged as one of the most innovative instruments in structured finance, offering a unique solution to liquidity issues while providing investors with diversified exposure to an underlying pool of assets. But what exactly are PTCs, and how do they function? Let’s dive deep into their structure, benefits, risks, and the lessons learned from their misuse during the Global Financial Crisis.

Concept of Securitization

To understand Pass-Through Certificates, you first need to know what securitization is. Imagine a housing finance company (HFC) that has given out many home loans. These loans represent future payments (EMIs) from borrowers, which the company will collect over time. Now, the company needs to raise money, but it can’t borrow more because of various reasons, like having already reached its borrowing limit.

In this situation, the company can still raise money by selling some of its loans to a separate entity known as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). The SPV then packages these loans into securities (financial products) and sells them to investors. These securities are called mortgage-backed securities because they are backed by the cash flow (EMIs) from the home loans.

The key point here is that investors don’t rely on the company’s financial health. Instead, their returns come from the EMIs (cash flows) paid by borrowers. Even if the company faces financial trouble or goes bankrupt, investors still have a claim on the loan payments through the SPV. This structure shifts the risk from the company to the pool of loans, making the investors’ primary concern whether borrowers continue to pay their EMIs.

Credit Enhancement and Tranching

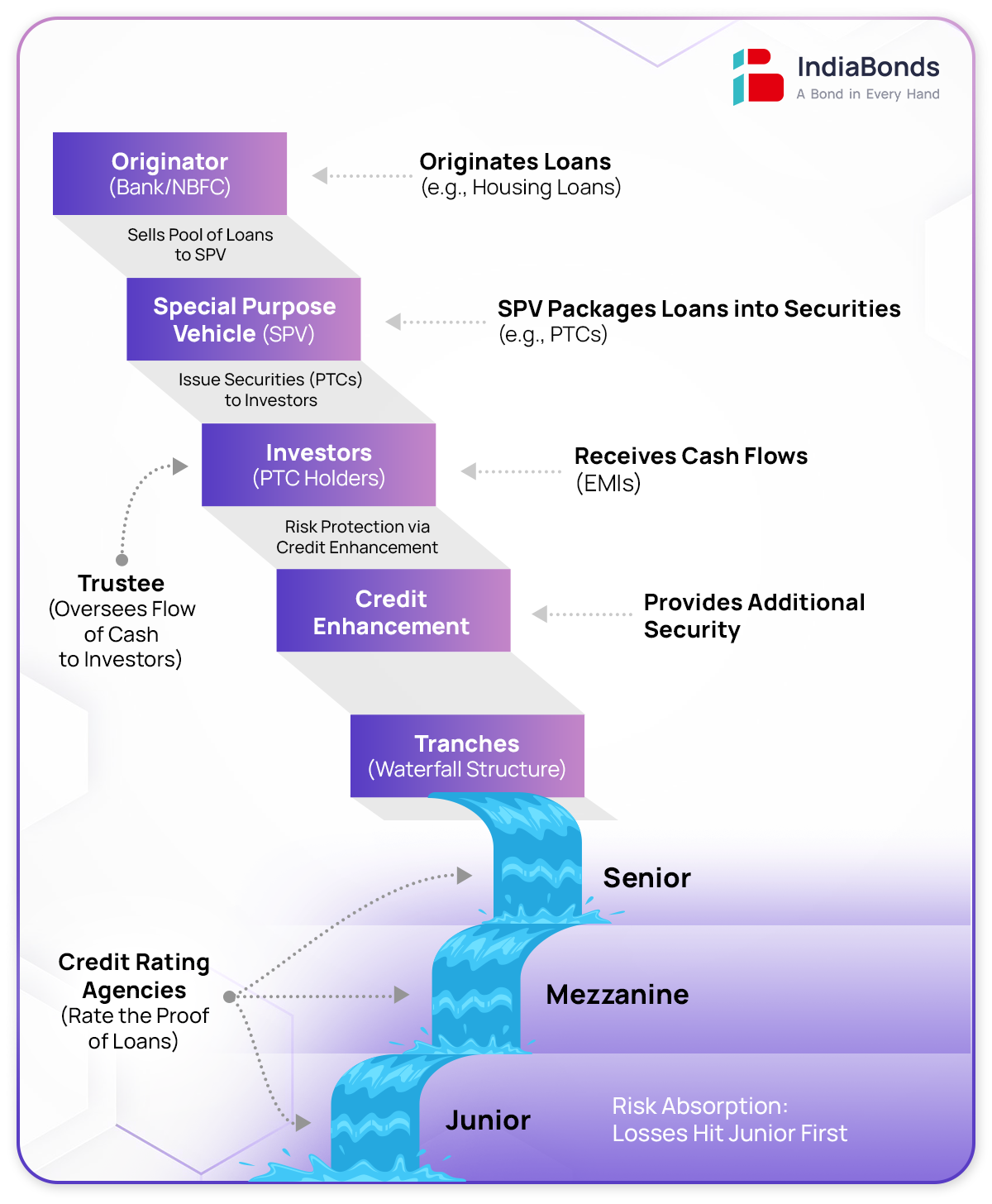

To further protect investors, securitization structures often include credit enhancement mechanisms, which are designed to improve the quality of the securities issued. One common method is dividing the loan pool into different layers, known as tranches:

Senior tranche: The safest layer. It gets paid first and only takes losses if things go really wrong.

Mezzanine tranche: This layer is riskier. It gets paid after the senior tranche and takes losses if there are defaults.

Junior tranche: The riskiest layer. It takes the first hit if any loans default. This system ensures that the senior tranche is protected unless there are many loan defaults. The junior tranche absorbs most of the losses. Each of these tranches is rated by credit rating agencies to reflect their risk levels. Senior tranches, which are the safest, often receive high ratings such as AAA, while junior tranches, being riskier, receive lower ratings. The credit rating acts as a form of credit enhancement, giving investors’ confidence in the safety of their investments based on the quality of the underlying loans and the level of protection in each tranche. This is the heart of the Originate to Distribute (OTD) model, where originators (such as housing finance company in our example) originate loans, but distribute the associated risks to other market participants, rather than being concentrated on a single entity through securitization.

What are Pass-Through Certificates?

Pass-Through Certificates are a form of securitized debt instruments. They represent a share in a pool of loans, where the investor receives a portion of the cash flows (such as interest and principal payments) generated by the underlying loans. These cash flows “pass through” the SPV to the investor, giving the instrument its name. In India, PTCs are most commonly used by Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) and other financial institutions to raise funds. They enable issuers to tap into a larger pool of investors, offering high net-worth individuals and institutional investors access to diversified asset pools. A distinguishing feature of PTCs is that they are typically structured as bankruptcy-remote instruments. This means that even if the originator defaults or goes bankrupt, the PTC holders still retain a claim on the underlying assets (such as housing loans, auto loans, or consumer loans).

How do Pass-Through Certificates Work?

The PTC structure is relatively straightforward. Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how they work:

Originator: This is the financial institution (such as a bank or NBFC) that has originated the underlying assets, such as loans or mortgages.

Special Purpose Vehicle: The originator sells the pool of loans to an SPV, a legal entity created solely for the securitization process. The SPV then issues PTCs to investors.

Trustee: A trustee is assigned to manage the entire transaction, ensuring the proper flow of funds. Their role is to guarantee that the cash flows from the loan pool are accurately disbursed to the holders of the PTCs.

Servicer: While the loan originator often handles the servicing of loans, an independent third party may be appointed for this task as well. The servicer’s responsibilities include collecting repayments from borrowers and ensuring these funds are promptly transferred to the PTC investors.

Credit Rating: Before the PTCs are sold, a credit rating agency assesses the risk associated with the different tranches of the securities. The senior tranches, which have the least risk, may receive high ratings, while the junior tranches, which are riskier, receive lower ratings. Investors: The investors, often institutional players or HNIs, purchase the PTCs issued by the SPV. They receive returns based on the performance of the underlying asset pool.

Regulatory frameworks ensure that there are safeguards in place to protect investors. For example, the RBI mandates that originators must retain a portion of the loans on their own books (typically around 5%), a practice known as Minimum Retention Requirement (MRR) (source: RBI). Additionally, in many cases, issuers provide overcollateralization to further safeguard investors. This excess collateral provides an additional buffer in case of defaults in the loan pool.

Benefits of Pass-Through Certificates

PTCs offer several advantages for both issuers and investors:

Liquidity for Originators: By selling off a portion of their loan portfolio, originators like NBFCs can free up capital, which they can then use to issue more loans, thereby expanding their business.

Diversification for Investors: Investors get access to a diversified pool of loans, which reduces their exposure to any single borrower or loan. This diversification can be particularly appealing in markets where the risk of borrower default is a concern.

Fixed Cash Flows: Investors in PTCs receive regular cash flows from the underlying loan pool, making it an attractive option for those seeking fixed income investments. Risk Mitigation: The tranche structure, credit enhancements, and overcollateralization offer protections to investors, especially those in senior tranches.

Risks of PTCs

While PTCs come with numerous benefits, they are not without risks:

Default Risk: If borrowers default on their loans, it can impact the cash flows passed through to investors. While credit enhancements and tranching help mitigate this risk, junior tranche investors remain particularly vulnerable.

Interest Rate Risk: Changes in interest rates can impact the market value of PTCs. Rising interest rates, for example, might make existing PTCs less attractive, potentially reducing their liquidity. Limited Liquidity: PTCs in India have limited participation from retail investors, and the secondary market for these instruments is not as liquid as for other fixed-income products like bonds.

What Went Wrong in the Global Financial Crisis and Lessons to Be Learned

The GFC was a stark reminder of the dangers of poorly regulated securitization. In the years leading up to the crisis, financial institutions created increasingly complex mortgage-backed securities, many of which were backed by subprime loans—loans given to borrowers with poor credit histories. The risks were downplayed, and investors were misled into believing that these securities were safe. When borrowers began defaulting on their loans, the losses quickly spread throughout the financial system, leading to the collapse of major institutions like Lehman Brothers. The GFC showed that while securitization can offer numerous benefits, it also comes with significant risks if not properly regulated.

Key Lessons

Transparency is Key: Investors need clear, accurate information about the underlying assets backing PTCs.

Risk Management: Securitization should include adequate risk management measures, such as credit enhancement and overcollateralization.

Regulatory Oversight: Strong regulation and oversight, like those provided by the RBI and SEBI in India, are essential to ensuring the stability of securitized products.

Conclusion

Pass-Through Certificates are a powerful financial tool when used with the right intent. They offer a viable investment avenue for institutional investors and high ticket investors pursuing higher yields and diversified exposure. However, PTCs should not be considered a core part of a portfolio. Instead, they should be viewed as an alternative investment option, and investors should be careful not to concentrate too much of their holdings in one asset class. Diversification, not just within the PTC structure but across asset classes, remains the key to managing risk.

FAQs

Q. How are PTCs regulated in India?

A. In India, PTCs are regulated by both the RBI and SEBI.

Q. What are the risks associated with PTCs?

A. PTCs carry risks such as borrower default, interest rate fluctuations, and limited liquidity. While credit enhancements and tranching help mitigate some of these risks, they remain particularly relevant for junior tranche investors.

Q. What role does the trustee play in a PTC transaction?

A. The trustee acts as a fiduciary on behalf of PTC holders, ensuring that the cash flows from the underlying assets are correctly distributed and that the terms of the securitization deal are followed. The trustee can also change the servicer if needed to protect the interests of the investors.

Disclaimer: Investments in debt securities/ municipal debt securities/ securitised debt instruments are subject to risks including delay and/ or default in payment. Read all the offer related documents carefully.